The result was much less schoolyard-ish, resulting in the new up-and-coming leader Hannibal to led Carthage in a siege of the city and Rome saying they didn't want it badly enough to bother going in and helping. Rome is really not trying for any honourable accolades as it seems. It took quite some time but Carthage eventually took Saguntum, much to the dismay of the inhabitants, many of which took their lives rather than face the Carthaginians. I suppose Carthage wasn't earning those accolades either.

|

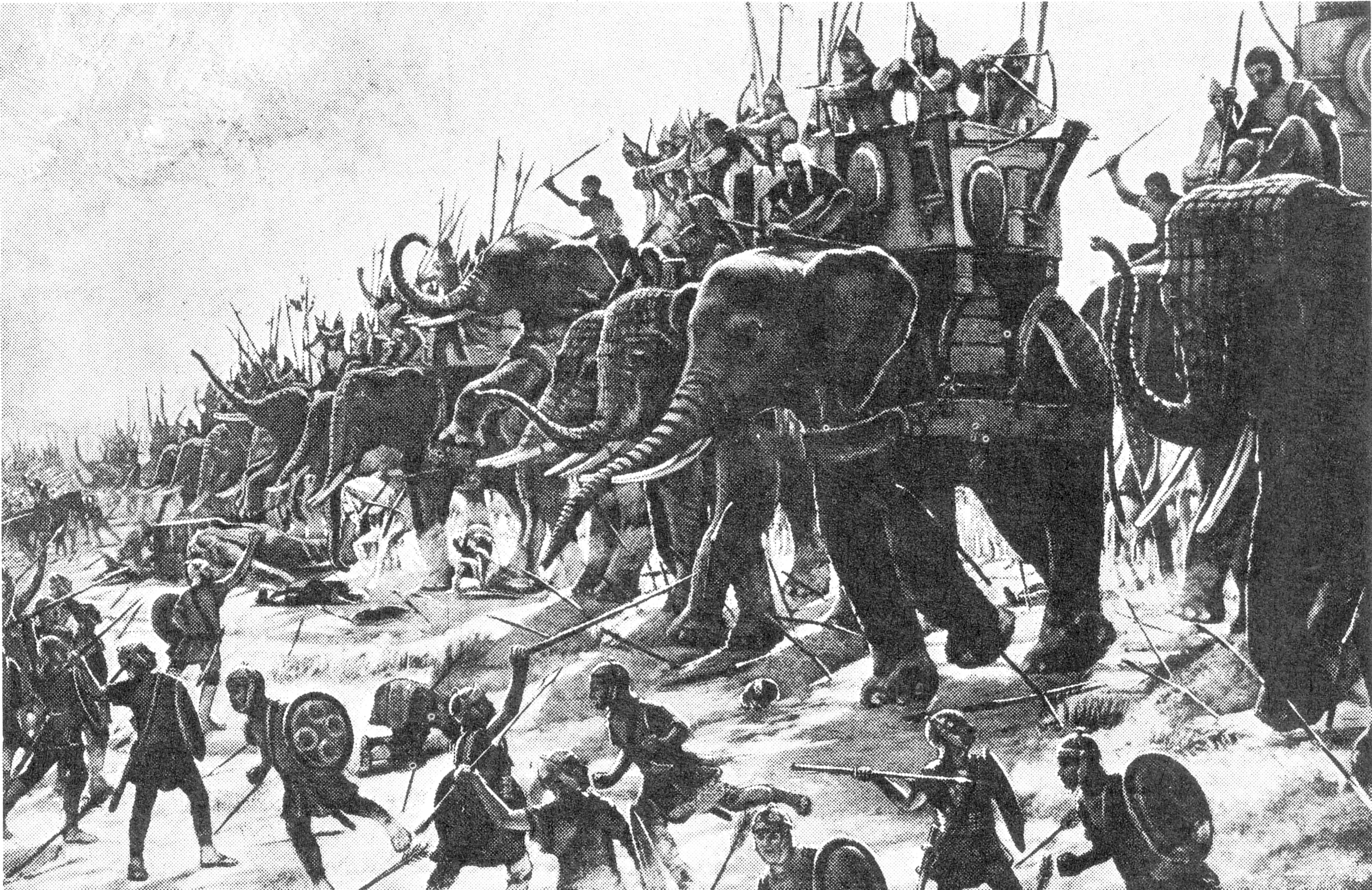

| I really can't get enough of the war elephants. In the words of Futurama... they have "elephants that never forget... to kill!" |

Meanwhile, Rome was anticipating the arrival of the moving land-mass of elephants, horses and men that was bent on their annihilation and deemed it appropriate to consider doing something about it. They sent out a force to meet the Carthaginians before they left the Iberian Peninsula, knowing that if they struck them before meeting up with the uprising Gauls they had a better chance at victory. Unfortunately, the Carthaginians proved elusive and they were unable to meet them on the field of battle. How they missed 100,000+ soldiers is beyond me, but it's important to remember that this was well before the days of GPS, and I took not one but two wrong busses on the way home today. I suppose I can sympathize.

|

| Hannibal crossing the Alps. At the top right you can see a particularly clumsy elephant. He wasn't going to win the war anyway. |

Further compounding the troubles back home for Carthage, Hasdrubal (the leader of the reinforcements that came too late) was about to find himself in another painful loss to Rome. Hoping to weaken the naval fleet of his enemy, but keenly remembering the many losses from the previous Punic war out on sea, he decided to move both his army and navy close together in a consolidated force. The purpose was to provide both moral support and a safe place to dock if need be. However, the army was hopelessly disorganized, and to put it as softly as I can, they were slaughtered. The most crippling result was a blockade between Roman soldiers and Hannibal, meaning the latter was off on his own without backup as no reinforcements could make their way to him. A few naval assaults were made over in Sicily, but bad weather and advanced knowledge on behalf of the Romans thwarted the attacks. Basically all eyes, and all Carthage hopes, were on their ruler with an admittedly giant army walking his way towards Italy.

Where everyone else in Carthage seemed like hopeless commanders, Hannibal was busy winning it almost single-handedly - along with, you know, his entire army. The Gallic tribes rose up against Rome and supported Carthage as was expected, the uprising being helped by Hannibal's army in the first place. Rome attempted to counter, but well timed ambushes slowed the Roman advance. The greatest accomplishment for Hannibal was yet to come, however; his next move involved crossing the Alps to catch the Romans by surprise, arriving much sooner than would be anticipated. Scoffing at the obvious difficulties, he brought 28,000 men, 6,000 cavalry and a number of elephants over the Alps with the help of native tribes and the Gauls. Rome has previously planning on moving on Africa, but the unprecedented speed on which they arrived set the entire plan back.

Carthage continued to fight (and win) in Roman territory, and as a result their army actually grew instead of dwindled; being unable to rely on the crappy leaders back home, he recruited more of the uprising Gauls to join him. The northern half of Italy was effectively in open revolt, seeing Hannibal as their leader. Wins kept on rolling in due to his exceptional military strategy; luring the Romans into an a trap at the battle of Trebia in which the defenders fought without breakfast and after crossing a cold river, also with the adding weight of a planned battlefield in which Carthage attacked with flanking forces as well, Rome lost 20,000 of the 40,000 that were in the fight. More and more Gauls joined, bringing the army to 60,000.

Hannibal was seemingly unstoppable, and rapidly approaching Rome. Tactically brilliant and with the force of the people on his side, the Romans prepared for the worst (the worst being losing the city of Rome - also dying). They heavily defended fortifications on the path towards Rome, but Hannibal simply moved around the flank and turned the tables on them, slipping past the enemy and effectively cutting off the Romans from their own city. Knowing that at this point they had to give chase and attack, the Romans moved right into the waiting hands of Hannibal's armies, ready and waiting in an ambush. They were slaughtered; cavalry was sent in afterwards but they as well were quickly defeated. A great number of prisoners were taken, the Roman ones being kept and the non-Romans were set free to spread "Carthage is saving you" propaganda to everyone that would listen. Rome at this point was a possible target, but ignoring his advisors Hannibal decided it would be too risky, the smarter move being to continue his plan of building up soldiers and biding his time. Hannibal was brilliant, but careful.

| A well-preserved road that was actually used by the armies of Fabius. I know it's just a road, but still... when you really think about it, it's pretty amazing. |

Well, the commander didn't... but the rest of Rome certainly did. They were eager for a large scale assault, and decided to double the army supply and take the force to Hannibal's door. Eager for battle, they charged the Carthaginians on a ground that was much better suited for Hannibal who once again planned his defence flawlessly. In the battle of Cannae, 50-70,000 Romans died or were captured, a colossal loss. The shaming resulted in Greek cities in Sicily being induced to riots as well, and several southern Italian allies moving towards the way of Hannibal. Directly after the battle, there was a brief path to Rome in which Hannibal would be relatively unimpeded, but the careful, tactical manner in which Hannibal attacked proved to work against him this time. He waited too long and missed his opportunity, much the way when one has to defecate but decides to wait for the commercial and then no longer has to go. Both result in the most profound of regrets.

|

| The caption on Wikipedia said it was Hannibal counting the signet rings of fallen Roman generals (which is really cool) but it just looks like he's standing there... |

Once again, Carthage was pitted with a massive war indemnity to slap around their economy even further than before. Their navy was limited to only ten ships, just enough to ward off pirates. Hannibal, meanwhile, became a businessman for several years until he was exiled to Asia where he continued to fight the Romans until he was cornered and committed suicide. It was not a fitting end for such a tremendous military tactician. But hey, he still lost, so... he couldn't have been that good.

What made the second Punic war seemed to be when an army chose to attack: if Hanno had waited for reinforcements, the Iberian front could have ended entirely differently; Hannibal's ambushes and luring armies worked wonders throughout his campaign; the Fabian strategy of persistent waiting was critical in Rome's eventual success, with the traditional run-up-and-fight strategy failing time and time again; lastly, Hannibal dropping the ball just one time meant that he missed his opportunity to take Rome. The second war really just came down to a matter of timing.

Famous Historical Figures Say the Darndest Things!

- "Carthage must be destroyed." The words of Cato the Elder. It sounds like it's not that great of a quote, but it's all about context. Cato would say this at the end of every speech, believing that Carthage would rise again if not entirely crushed. Yes, every speech, even if it had absolutely nothing to do with Carthage.

- "Let us relieve the Romans from the anxiety they have so long experienced, since they think it tries their patience too much to wait for an old man's death." Hannibal's last words, apparently realizing Rome was not particularly fond of him. He was not to be later reunited with Scipio on some ancient version of Maury.