|

| The art on Alexander's sarcophagus. Even in death, he's trampling and conquering Persians. |

At this point Alexander's lands were massive, but he still desired more. They would continue travelling to India, towards the ocean and his final goal. He would take a stone to the neck and an arrow to the leg in getting there, furthering the number of wounds Alexander took on his expedition- but that wouldn't stop him. There were plenty more lands to conquer, but for the first time he was beginning to run out of steam. Cavalry could no longer be brought along with the same numbers as they were taking up too much food, and were pretty well replaced with Asian soldiers. This upset his original Macedonian army, as they saw him as becoming too lenient towards Persian ways; his army had a very, very large Asian contingent, he began to dress in a more Persian manner, and he began dropping hints that his men should get with some of the Persian women - making him somewhat of a conquering Cupid. The men were not interested in such an arrangement, however, and the "new and improved" soldiers were not welcomed with open arms by Alexander's old guard.

On one particularly hot night, with tempers flaring and alcohol not in short supply, he got in an argument with one of his Macedonian generals, Cleitus (not Cletus, of Simpsons fame). Alexander had been boasting about his accomplishments, perhaps without giving enough credit to his incredibly loyal Macedonian army who have really put up with a lot at this point. This enraged Cleitus who called him on it, starting a yelling match between himself and the king. Alexander took one of the swords of his guards and stabbed Cleitus, killing him during his drunken rage - an action that would both lead to a great deal of regret for Alexander, as well as furthering the rift that was already growing between his old soldiers and himself. Those soldiers, however, realized that if they were to desert, they didn't really have anywhere to go. Unfortunately for them, they were stuck there, remaining with their leader not entirely out of loyalty anymore, but also out of necessity.

|

| The death of Cleitus. It was the first cause of overacting in an artist's depiction of a historical event. |

In spite of the difficulties, Alexander continued to march to India with 15,000 Macedonian soldiers still with him, but a vast army of Asians with him as well - their numbers are terribly uncertain, but can be as low as 20,000 to as high as 120,000, depending on your source. Realistically, it's probably somewhere in between, but it's important to know that the Macedonians are definitely in the minority, although they still have the highest positions in the military.

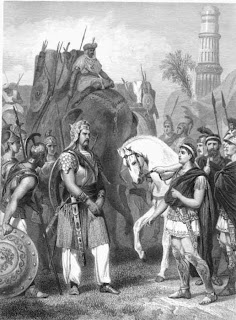

His first contact with an Indian army was with a warlord named Porus, with a large supply of elephants and a larger supply of men. Elephants were difficult to fight as horses would be terrified of them and thus wouldn't charge towards them, preventing them from being used as a shock tactic. Even though Alexander's supply of cavalry were dwindling, they were still a critical part of his army, and the battles against Porus proved difficult. They still, however, emerged on top - but with a number of casualties including the death of his beloved horse. During the battle Alexander personally killed Porus' son - which makes the next part exceptionally strange. After the battle had finished and the Indian army was mostly defeated, Porus and Alexander spoke and discussed terms. Porus, a large and imposing man refused to be treated like anything else but a ruler in spite of his defeat, which impressed Alexander, prompting them to create somewhat of an alliance. This happened shortly after Alexander killed his kid and ravaged his army. It was a different time back then, I guess.

Continuing through India finally (finally!) pushed the Greeks over the edge. By now they have been starved twice (!), killed an estimated 750,000 people (!!!), and travelled 11,250 miles over their campaign (!!!!!), but it was the weather that finished them (?). Three months of rain mixed with massive snakes and scorpions slowing their advances proved to be the straw that broke the admittedly patient camel's back. Alexander tried to rouse them to continue, but they would finally be hearing none of it, and they finally began their return trip home. Unbeknownst to Alexander, they were just 600 miles short of the ocean, their goal. So that old quotation you hear about Alexander weeping for there were no lands left to conquer? Yeah, that's bogus. Ultimately he went home unhappy as he had not yet seen the end of the world.

|

| Porus was huge and fought beside elephants. I'm terribly confused how he lost this fight. |

The return trip home - in which the Macedonians went to their true home and Alexander to Babylon, which in itself is telling of Alexander's turn towards Persian culture as time wore on - was just as fraught with peril as the conquest itself. They still had to fight through Indian warriors slowing their retreat, but the Greeks were so tired and weary they almost refused to fight. One battle found Alexander charging in with just a few soldiers to shame his men into following him. The charge almost cost him his life as he was separated from the group, taking an arrow in the chest shortly after that almost killed him.

It wasn't just soldiers that were killing the army, though - drought, floods, snakes, poisons... everything in existence was felling them in some regard. In their return, they had 85,000 people (including non-combatants) which slimmed down to a meager 25,000 in the sixty days they took crossing the desert - but they did make it home, but only to a vengeful, angry and paranoid Alexander. He began to purge a number of his commanders whom he did not believe to be loyal, stretching the rift between him and his men further. The strongest blow to Alexander's psyche came at the death of his beloved Hephaestion, causing him to go on a rampage and slaughter a massive number of Cosseans - a warrior tribe independant of Persia - as a sacrifice to his spirit. In the wake of his grief, he drank more than ever before (which is saying something) which led to his death, likely caused by a mix of malaria made worse by the excess of alcohol. That, or poison. That was a possibility too.

Alexander the Great died at the age of 33. He left successors, but no heredity. Soon his lands were split apart and his empire fell just ten years after his death. But that isn't to say he didn't leave a legacy - he sent back an incredible pile of riches, became one of the most powerful men to have ever lived, and from what it sounds like, drank more in his 33 years than ten men would in their lifetime.

_______________________________________

The information for this blog was taken from "Alexander the Great: Journey to the End of the Earth" by Norman F. Cantor.

_______________________________________

The information for this blog was taken from "Alexander the Great: Journey to the End of the Earth" by Norman F. Cantor.