Roman. Died in March.

That's pretty much all I knew about Caesar going into this. Historical relevance doesn't grow with age, and anything that happened before the time of Christ (Caesar's life was around the last century B.C.) might just slip through the high school history textbook cracks. Well, in all fairness most of what I remember from my grade school social classes were heaps of fur trade information and the occasional unit on countries seemingly chosen out of a hat (Brazil, Russia and Japan to name a few).

.gif) |

| I really wish the eyes didn't look like that. |

His family was not the most prolific and didn't hold the most political sway, but they were still somewhat high on the totem pole. He became a high priest of Jupiter, but quickly lost that position as changing powers in the republic (usually resulting in bloodbaths comprised of the political opposition) meant he had to step down and lay low for a while, giving up his dowry and inheritance in the process. Eventually his family bargained with the ruler at the time, and he left Rome to join the army without major fears of prosecution; this was indirectly a result of having been ousted from the priesthood, as he could never have been leading an army in that position. Priests of Jupiter are not allowed to touch a horse, sleep three nights outside his own bed (or one night outside Rome) or look upon an army - the last one being particularly difficult for someone hoping to be in the military.

Hearing of the death of the ruling power and hoping for a little more lenience in the new leader, Caesar returned to Rome. He began to learn the legal and political ropes and quickly rose to prominence due to his excellent oratory skills and his open hatred of corruption and extortion, common problems in the Roman political sphere. Eventually he was sent to rule over Spain, and in what would soon be known to be a rather typical trait of Caesar, he acquired some very large debts - he wasn't particularly good with money, and had the same ability to over-spend as a present day shopping crazed teenage girl with a credit card. Fortunately, he had a friend in Marcus Licinius Crassus, which most of the aforementioned teenaged girls do not. He bailed out Caesar, a reasonable favour considering he had backed Crassus politically against his rival, Pompey - but more on that rascal later.

|

| He didn't rule with an iron fist - just a claw, apparently. |

Caesar then began to earn his reputation of being a man of the people. He proposed a law for the redistribution of public lands to the poor, which went through mostly due to the powers of the Triumvirate. Pompey, using his military powers, lined the city with soldiers to make sure no one would speak against it. Regardless, one man in the senate was vocally opposed and in turn he was beaten. Oh, and they threw some crap on him. The whole event had two results; Caesar was loved by the commoners, but in turn he was losing the favour of many of the status holding men - ancient Rome's 1%, basically.

Eventually his consulship ended, resulting in Caesar becoming a governor. In typical Caesar fashion, he was terribly in debt, but he knew military adventures were a good way to find some of the coin he's lost. He then went out to conquer Gaul, in which have been increasingly more frustrating to the powers of Rome as their Germanic tribes were becoming powerful and occasionally defeating Roman armies. However, they were crushed by Caesar, solving his money woes and expanding the borders of Rome quite significantly. It was, however, a fairly long expedition and there were troubles back home. The Triumvirate was dead - literally and figuratively. Crassus was killed in battle and Pompey's Caesar-given wife died in childbirth. Pompey then married a political rival of Caesar, and Rome was on the precipice of civil war. It makes you wonder what would have happened if Pompey's wife/Caesar's daughter didn't die plopping out that kid.

Pompey demanded Caesar disband his army in Gaul and return to Rome immediately. Caesar, not particularly inclined to taking orders and calling off militaries, crossed the Rubicon (the frontier boundary of Italy) and marched on Rome with only a single legion. While one legion is not particularly strong, it's significantly quicker than vast armies, and Caesar's legion was able to drive Pompey and the senate from Rome as they were unable to field an army before he arrived. Although Pompey did eventually find the army he was looking for, he was defeated at the hands of Caesar. Sometime after, Caesar gained more political power and eventually became a dictator.

There was, however, a matter of the senate and all the others who fled. Cato, a prominent member and a political enemy of Caesar's since his run for consul, was still at large along with Cicero and Cassius, friends of Pompey. United against him, Caesar had to defeat their armies as well, which he did quite successfully. Although Cato committed suicide upon realizing his defeat, Cicero and Cassius went to Caesar apologetically. Oddly enough, he not only pardoned them but gave them pretty decent positions. Say what you want about him, but he wasn't big on grudges and he kind of had a thing for mercy. Huh. Not the typical dictator. He also pursued Pompey to officially end the civil war, but found out that in a sense the job was done for him; Pompey, fleeing to Egypt, was then assassinated by the residents thinking they would gain favour with Rome. Caesar mourned the loss and turned the tables on the assassins and had them executed. Apparently Caesar thought of the civil war as a mere squabble between some old friends... which, you know, cost the lives of thousands. But still.

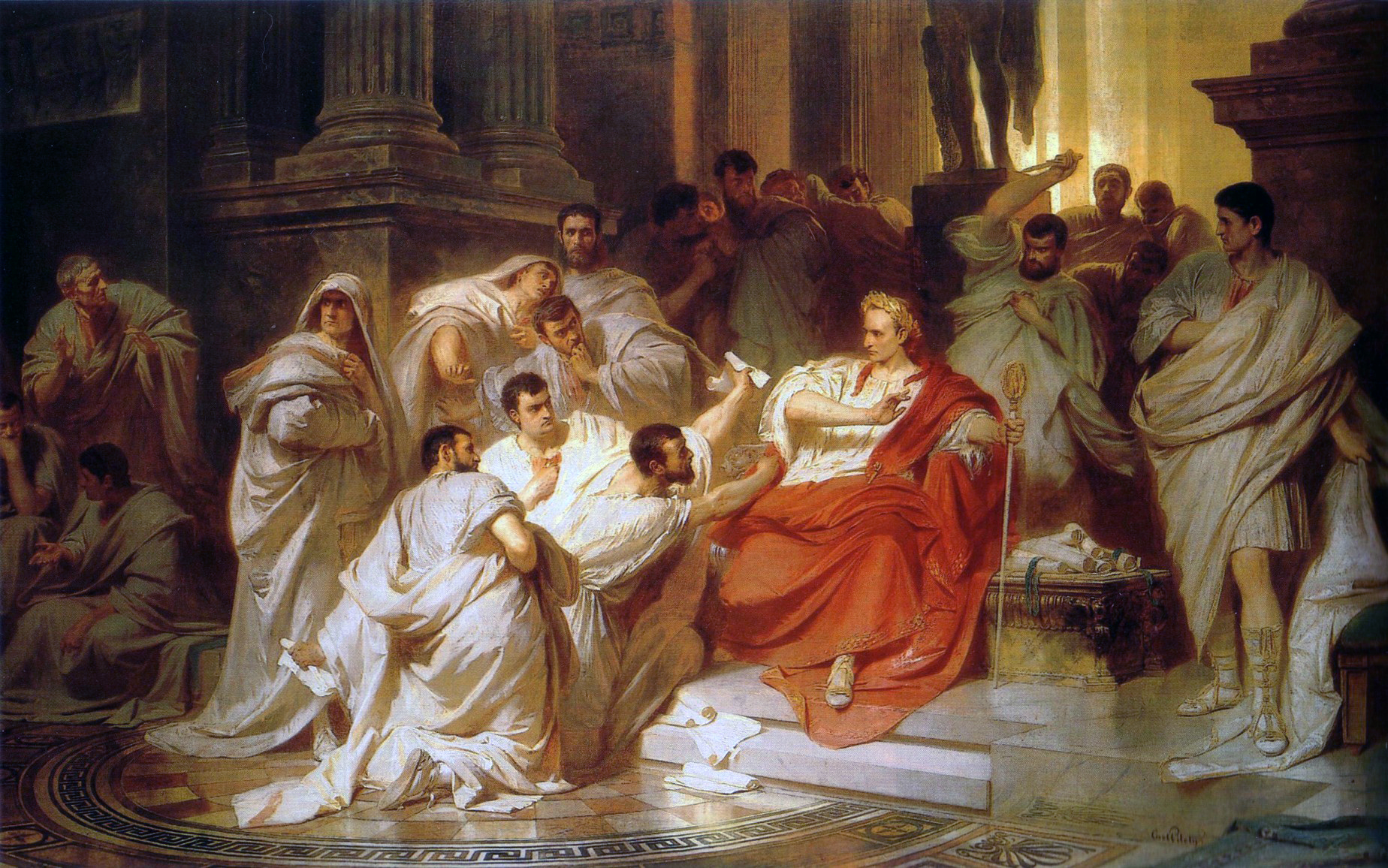

|

| Caesar, looking mildly perturbed by his murder. |

You see, it wasn't forgotten that Caesar was a man of the common people but not that of nobility. The senate did not favour Caesar, and previous hatreds refused to die out. Brutus and Longinus, two men who had favoured Pompey's side in the civil war, were pardoned by Caesar. However, this wasn't enough, and they planned his murder, a vicious group-stabbing (significantly worse than a regular stabbing, as this one included many more stabs). Their plan succeeded, and with a multitude of stab wounds the dictator was no more.

To the dismay of the assassins, the lower and middle class of Rome was enraged. His funeral resulted in a riot fuelled by the outrage caused by the death of who really was the people's champion. Eventually, his death led to the beginnings of the Roman Empire. Honestly, after reading all this I feel this was one of the few major historical figures who was actually a good guy. He pardoned his enemies, advanced the social and economic status of his homeland, respected his veterans who fought for him, and opposed political corruption. Caesar came to power without simply walking over those beneath him. I'm sure most would agree - save for that guy who had the crap thrown on him.

Reports are unconfirmed whether or not Julius Caesar would like the salad or the smoothie shop similar to him in name.

Famous Historical Figures Say the Darndest Things!

- "The die is cast." Caesar said these words after crossing the Rubicon to begin the civil war with Pompey. If you don't have any short phrases that carry a great deal of significance, you're not a historical leader. They've all got one.

- "Veni, vidi, vici." Meaning "I came, I saw, I conquered," this is one of the first instances of someone saying "eh, no big deal" after doing something that is, in fact, a very large deal indeed.

- "And you, son?" This was spoken to Brutus, and supposedly the last words Caesar spoke. Shakespeare's version is the more popular "et tu, Brute?" meaning "you too, Brutus?".

No comments:

Post a Comment